Today in my office, I’m listening to the live album Afro Blue Impressions by John Coltrane, recorded almost 60 years ago to the day, in Stockholm and Berlin. The sound quality of the recording isn’t stellar– if I recall correctly, the source tape is originally a two-track recording made by a fan — but it represents to me, one of the most potent distillations of the Classic Quartet’s power. Loose, transcendent– equal parts melancholy and joyous. Elvin Jones flails away like a madman throughout, McCoy Tyner is relentless and Trane is nestled in that sweet spot somewhere between terra firma and interstellar abandon. It’s also got a pretty kick ass 21-minute version of My Favorite Things.

When I listen to this album, I think of my Dad. He loved jazz. And growing up, I absolutely hated it.

Our relationship was a lot like that. In so many ways, Dad and I were like oil and water.

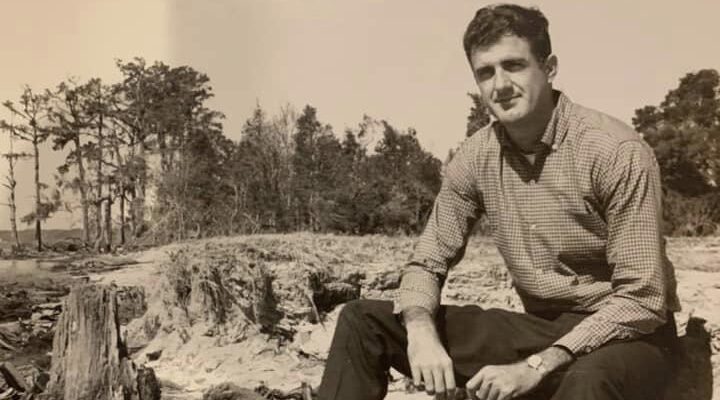

He was raised in poverty, during the Great Depression, to immigrant parents. I was raised in suburbia, went to private school and had a pretty comfortable upbringing. My Dad grew up desperately wanting to serve in the trenches in WWII, and missed his chance by just a few years. I grew up wanting to be a rock star. My Dad was a church-going, staunch, right wing conservative. Even as a very young kid, I thought church was a joke. And in my teens, was fairly left-leaning and anti-establishment. (Side note: When I was 17, he and I had something close to a knockdown-drag-out at the Sea Shanty in Coral Gables, over MLK and the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement. My dear Uncle Nick had to keep shushing both of us, because people in the restaurant were turning around. Good times!)

As a parent, he tried to steer me towards the Church and our Greek heritage. Towards William F. Buckley and Ronald Reagan. Towards vegetables and low sodium foods. Towards a stable career, with a good retirement package. I resisted all of the above. Especially in my youth. And from very early on, I could feel a resignation in my Dad about me. Things were never going to be the way he wanted them, and he knew it.

Dad hated rock n’ roll.

He didn’t understand it. He thought it was vulgar and derivative. He used to perform this mockery of what the average rock song sounded like to his ears. I would typically be treated to this performance when he walked unannounced into my bedroom as I was blasting AC/DC or KISS from my Panasonic boombox. It’s impossible for me to adequately describe his exaggerated imitation– hands clenched in a mock seizure, mouth open, yelling like a cartoon caveman. It’s also difficult to describe how much it used to annoy me.

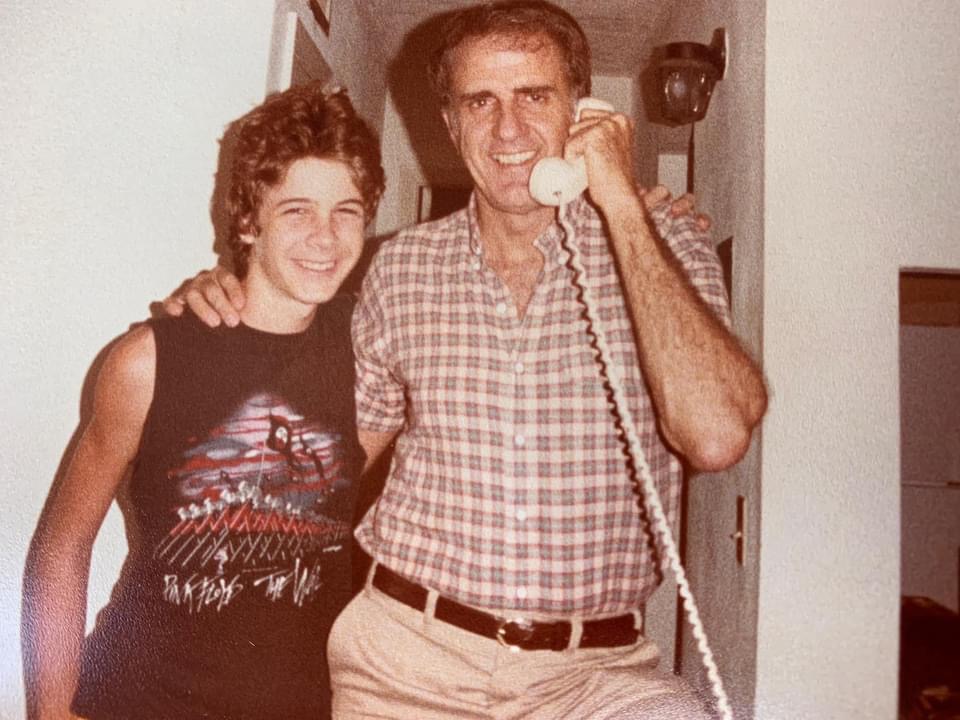

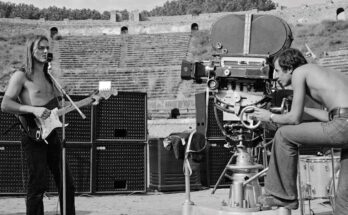

Which is why it was so unusual, when he walked into my room one Sunday afternoon in December 1982 and asked me, “Hey, do you want to go see that Pink Floyd movie [The Wall]? It’s playing at the Riviera.” The Riviera was a landmark South Miami theater, known for showing foreign films and other arthouse fare.

I didn’t know anything about the movie, in fact I wasn’t entirely sure who Pink Floyd were– I was only 13 at the time and they hearkened from a slightly earlier era– but the movie poster looked cool and I agreed to go. As it turned out, that Sunday matinee became one of these pivotal moments in my childhood, that transformed the way I thought about music and film and single-handedly birthed in me a lifelong love of Floyd, WWII history and all things Great Britain.

It’s not a great film. At all. But at some point about 30 minutes in, I silently glanced over at my Dad, half expecting him to be doing that cringey rock n’ roll mockery again, and he was actually crying.

The strangest thing of all, was that he told me on the drive home how much he liked the movie. Dad didn’t generally share his emotions openly, about anything. Some of the music was undoubtedly “out there”, he said, but “parts of it” were actually “beautiful”, he admitted. We went out to eat afterwards at a popular fried chicken-n-tacos place on 97th Avenue called Chicken Unlimited, and we discussed the movie through the entire meal. He talked about Vera Lyn– who is name-checked in a particularly poignant part of the album’s narrative– and the War. I talked about Gerald Scarfe’s cool animation and how I needed to go buy the album– which I did the very next day as I recall.

My Dad was stationed in England for two years during the Korean War. For the rest of his life, he would talk about how much he loved the Brits and British culture. He was also a WWII history buff. The Wall features both a distinctly British view of post-war Europe and a respectful, wistful remembrance of those who fought in that conflict . I think those were the hooks that drew him in. The story’s setting was a bridge for Dad to open up to music that he didn’t particularly like. And that shared enjoyment in the theater was a way for my Dad to connect with his weird, 13-year old son. It was a great moment.

Our relationship for the next 40 years, was…complicated.

Unfortunately for those on the outside, there was no user-friendly version of this man. He was frustratingly complex, prone to the hermit’s lifestyle and frankly, at various times, one of the most difficult personalities on the planet. He was also creative, had a wicked, self-deprecating sense of humor and at odd times, had the introspective disposition of a poet or painter. My sister and I grew up, forced to learn the calculus of his personality— and with each successive decade I felt like I was on the cusp of finally cracking the code. Almost.

We would sadly never see eye to eye on politics and religion. And those were monumental, immovable objects in my Dad’s life till the very end. When I inexplicably became very religious, in the late 80’s (and remained so for nearly 20 years), fate dealt my Pops a harsh blow by making me an Evangelical fanatic and not a Greek Orthodox like him. Dad hated Evangelicals. He thought it was Christianity-lite and he thought they were all Elmer Gantry, snake oil salesmen. When I mentioned that I taught the Bible in church, he didn’t want to hear anything about it. It was too much for him to bear. For a while there, things were really bad between us.

But music, especially jazz which I later came to love passionately, was always a shared pathway back to each other. A familiar bridge between our rival cities.

No matter how heretical I became in his eyes, or how far Right he became in mine, we could both talk about Ellington at Newport in 1957 and about Johnny Hodges playing “I’ve Got it Bad and That Ain’t Good”, and be deeply moved. Or Dexter Gordon’s Tanya. Or Art Tatum. Or Philip Glass’ soundtrack for Koyaanisqatsi.

As I got older and dove deeper into jazz, the number of these touch-points became greater. We had more to talk about.

In his final years, as he struggled with dementia, I would have long and mostly annoying conversations with him about nonsense like the trees outside or the length of the curtains in his living room. When I got exhausted with this, I would steer the conversation to jazz and things would smooth out. I would play the classics for him– Sidney Bechet or Oscar Peterson or the trusty Duke– and for a moment he would emerge from the chaotic fog in his brain and be himself again. He’d relax and the fight would leave him. Sometimes he’d just lean back and say “Man, oh man.”

In the final stages, when he no longer remembered who I was and had trouble speaking coherently, I played a favorite, shared Louis Armstrong moment for him on my iPad and he wept profusely, unable to speak. All he could do was repeatedly tap on the screen with his finger as if to say “THAT RIGHT THERE, BROTHER!” All I could do was lean back and soak in the moment. Man, oh man.

That “bridge” to reach each other was always there. It still is.

Happy Birthday, Dad!!!