In April 1984, when I was just 15 years old, I spent an entire Friday night and Saturday morning curled up on the sidewalk in front of Spec’s Records in Kendall Lakes in order to get tickets to see David Gilmour on his About Face solo tour. Gilmour wasn’t just my favorite guitarist—he was my creative North Star.

Dizzy Gillespie was once interviewed about the importance of his musical hero, Louis Armstrong. Gillespie told the reporter simply, “No him, no me.” Without hyperbole, I feel the same way about David Gilmour.

Sure, Frampton, Frehley, and Van Halen (in that order) were the early inspirations in the late 70’s that compelled me to swap my tennis racket for a real guitar. But Gilmour showed an adolescent me what was really possible. His playing transcended the stereotypical posturing and showmanship associated with most rock-n-roll guitarists. Gilmour seemed completely unconcerned with that stuff, and that resonated with my youthful idealism. His playing wasn’t about ego, it was about storytelling. Instead of instrumental flexing, Gilmour used an impressionist’s palette and invited listeners on a cinematic journey, by way of textures, subtle noises, unusual effects, and restrained and lyrical playing.

Before 1984, the last time Pink Floyd had played in South Florida was at the Miami Baseball Stadium in 1977, for the infamous Animals tour. I missed that one. When PF announced in 1983 that they were going on permanent hiatus, I realized the chances of catching a show in my lifetime were practically nil. Determined to get good seats to see the next best thing — a solo David Gilmour– I concocted a flimsy story for my mom about staying at a friend’s house that night. She didn’t believe me but dropped me off anyway. “Be careful!” she yelled out the car window as her cool, little Mitsubishi Starion peeled off into the night.

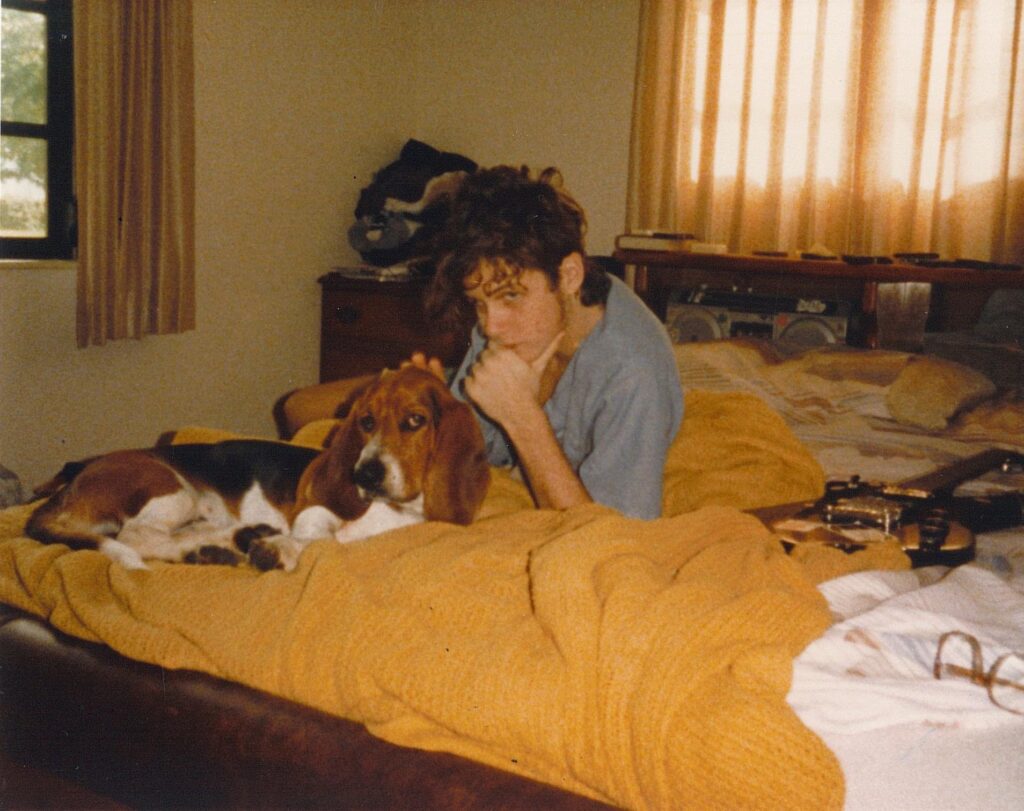

I arrived at Spec’s Records that night clothed in my ripped jeans and a Wall “marching hammers” T-shirt; armed with an obsession no one else in my circle quite understood.

The store was still open when I got there, so I went inside and milled around awkwardly for a while; pretending to shop. I said hello to Skippy Hood, my goofy, hipster English teacher at Miami Killian Senior High, who also managed Spec’s in the evenings. I then went outside and leaned against the storefront window, like I was waiting for someone. I wasn’t entirely sure how this “camping out” thing was supposed to work. Where was I expected to line up? What would I sleep on? Who else would be there?

As the surrounding shops in the outdoor mall all closed, one by one, and shop owners drew their awnings and locked their doors, I braced myself for the lonely night ahead. The prospect of adversity and discomfort were inconsequential to me. I had to be first in line. As it turned out, I was the only line for the entire evening.

As the brisk South Florida evening dragged on, no other Gilmour fans arrived. Why didn’t people care??? Winos and other creatures of the night wandered past me all evening– each one invariably asking me two questions as they stepped over my shivering body: “Hey kid, what are you doing?” and “David WHO???”

I probably slept ten minutes that night. I was cold. And bored out of my ever-loving mind. At some point, I left my coveted spot at the front door and paced around the open mall. I got drinks from the water fountain near the mall’s K-Mart. Then I returned to the front door of Spec’s, and repeated this cycle a dozen or so times. I bounced rocks off the wall. I looked inside garbage cans for anything interesting. I pissed in the landscaping. Then I laid back down in a semi-fetal position and tossed back and forth, as my spine sought for a sweet spot on the mall’s dirty pavers. Despite all the privations that came with camping out for concert tickets in the 80’s, I was as happy as a clam. After all, I was gonna SEE DAVE, DUDE!

Long before YouTube or Insta reels, my only chance to actually see David Gilmour perform live was via a cherished VHS copy of Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii (1972).

AJ, was a friend and fellow Floydian who lived a few blocks away from me as a kid. He and I found the VHS tape of Pompeii one afternoon at West Coast Video in Kendall Lakes, but the $45 price tag was outrageous for two broke 9th graders—equivalent to about $150 today. AJ came up with the idea for the two of us to start a mobile car wash and earn the money for the tape over the course of one Saturday.

Dragging around a bucket, several large sponges, and an industrial-sized bottle of Palmolive dish soap, we knocked on doors in Sabal Chase, offering neighbors $5 washes. I was terrible at that shit—far too timid to be assertive with strangers and way too lazy to ever get the job done by myself—but AJ was a natural-born salesman. And a hard worker. After a long afternoon cleaning BMWs and Celicas, we had the cash. For the next few years, we had joint custody of the Live at Pompeii tape. When his mom sent him away to military school at some point in 1984, I was awarded sole custody.

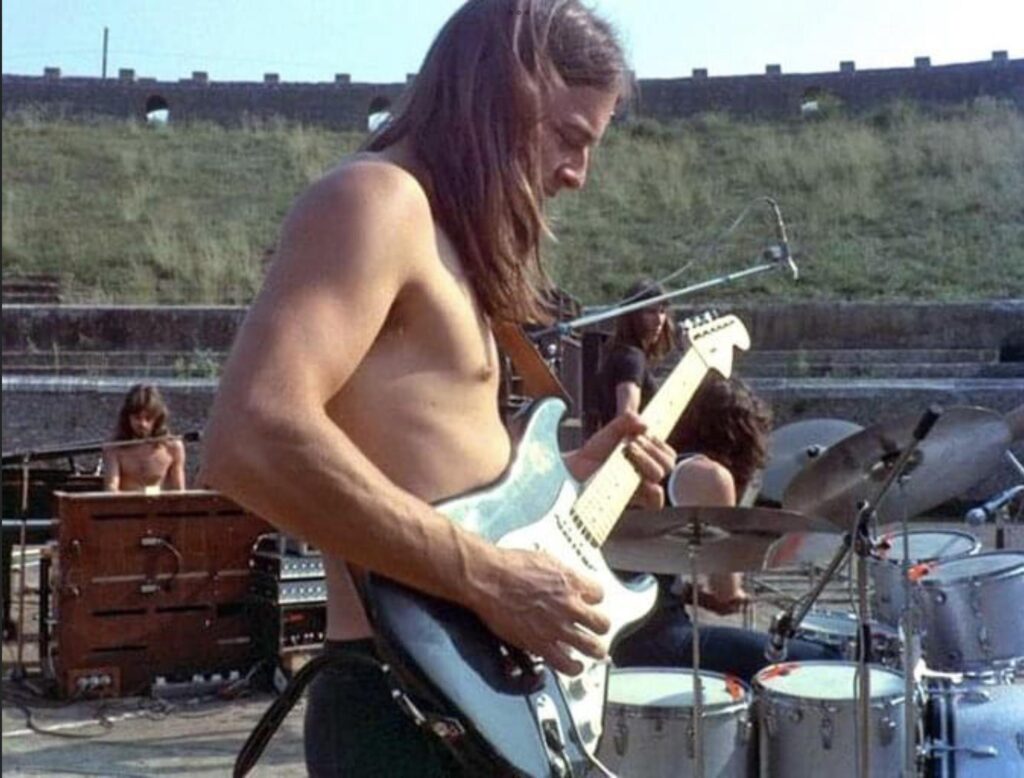

That film became my holy grail. It showed Pink Floyd playing pre-Dark Side of the Moon classics in the eerie, empty amphitheater at Pompeii, interspersed with bubbling volcanic vents and close-ups of haunting Pompeiian frescoes. With almost any other band, this threadbare concept for a film would be like watching paint dry, but Floyd’s music seem to thrive in the ancient silence of those ruins. For much of the film, Gilmour just stands like a Pompeiian statue in the center of the open coliseum, his unorthodox tools lying in the sand around him– a mustard-colored Binson Echo unit, a Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face and a stack of Hiwatt DR103’s. The performances showed Floyd at the top of their early-career game. And Dave looked cool as fuck. Thanks to the magic of VHS and the ability to be able to pause and rewind, I got to see the maestro up close. I studied how he coaxed those ghostly sounds out of his instrument– the simple right-handed slide technique that sounded like a violin in outer space, was a revelation to me. I stole that technique wholesale and deployed it immediately in my own garage band jams. I also studied those trademark half-step bends, the roars and pitched wails of Saucerful’s “Syncopated Pandemonium” movement, the prehistoric bird scream in the middle section of Echoes, etc… It was all magic to me.

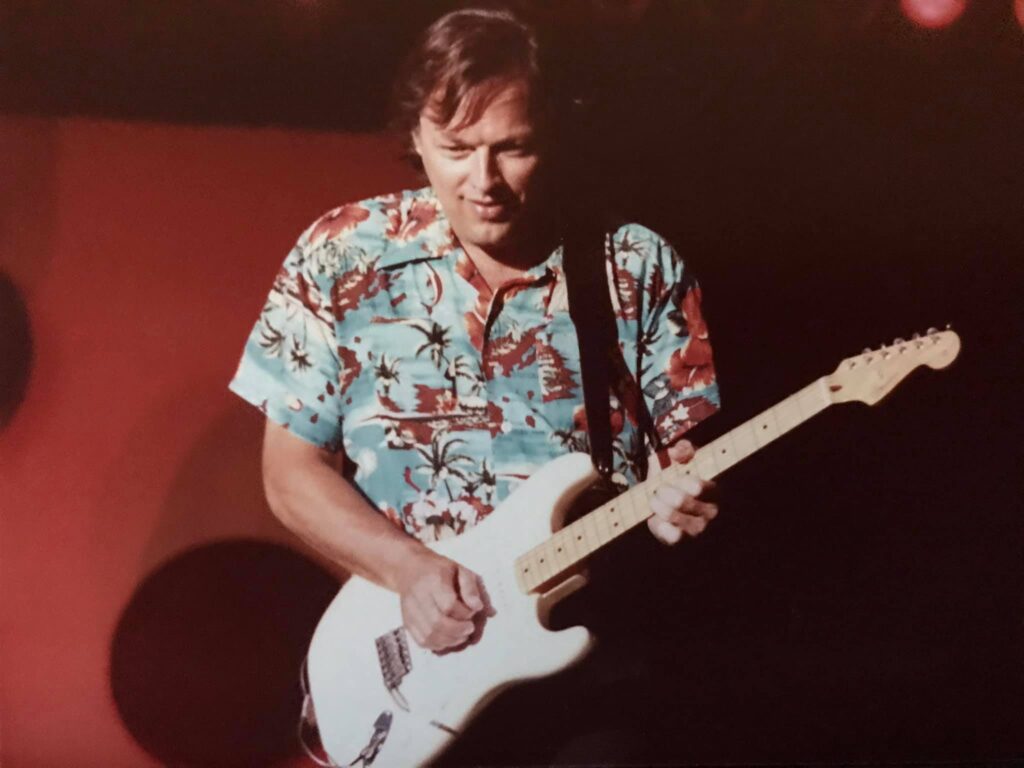

The middle-aged, more pedestrian and slightly-receding version of Gilmour that I would get in 1984 at the Sunrise Musical Theater, was a far cry from that enigmatic figure in the film.

I got no 21-minute version of Echoes. No extended avant garde freak-outs like Saucerful of Secrets. None of the foreboding build-up of Careful with That Axe Eugene. By the time 1984 rolled around, Dave was a proper English gent, prone to wearing Hawaiian shirts and focusing strictly on his solo material– with middle of the road, FM-friendly tunes like Love on the Air, All Lovers Are Deranged and the 80’s dancefloor horns of Blue Light, at the fore.

It didn’t matter to me. $14.10 bought me a second-row seat to see the man. I would sit no more than 12-feet away from him for two hours. This bested any rerun of a VHS tape, by orders of magnitude.

Some dismiss this 80’s era as a low point in Gilmour’s career. In my book, he was still the King, and that July 5, 1984 show remains one of the most transformative events of my youth.

Having said that, there was a mild devil’s advocate hangover after the event that told me I’d only seen a diminished Gilmour; a quasi-cover band, car show rendition of PF. I never could quite shake this mild pessimism. His band for that tour were undeniably goofy—and not in a cool way– and the whole gig had that plate reverb 80’s sheen that felt a little incongruous with his best work. I knew it. I felt it. But I never allowed myself to admit it out loud.

In the intervening years, Gilmour’s music has only become more important to me. Even the cheesy stuff.

Over the past four decades, life unfolded in its messy, unpredictable way. I played in a band, started writing and recording music, and even toured the eastern U.S. briefly. I graduated high school, dropped out of college, got married, had kids, changed careers a few times, and got divorced. My kids grew up. I went bald. I got remarried. Through all of it—good times and bad—Dave’s music remained an immovable refuge for me, a sanctuary city.

Even the oft-maligned post-Waters Pink Floyd and Gilmour’s more unassuming solo material has gathered emotional gravity over time. The songs just mean more to me now. Tunes that felt lightweight in 1984, like Love on the Air, now shine with an honesty and simplicity that feels poignant. The cheesy Yamaha DX7 keyboards, dated production, and lack of edge hardly matter anymore. When I hear it, I’m transported—back to 1984. In that safe space my beloved grandmother is still alive, the burdens of adult life have yet to cast their shadow over me and life feels wide open and brimming with possibilities.

Earlier this year, when Gilmour announced a new album Luck and Strange, and a handful of shows in LA and NYC in what is very likely his final tour—I felt compelled to make the pilgrimage one more time. Forty years after that fateful show in Sunrise, I was ready to brave discomfort for one last chance to see him. I’m 55. Gilmour is 78. Who knows what the immediate future holds?

The NYC shows were announced at this uncomfortable crossroads in my professional life. My feelings about my job were at all time low.

At the beginning of 2024, the office building I had worked in for 13 years was suddenly deemed “uninhabitable” and marked for demolition. Staff were quickly relocated to trailers, offsite. Because our data and networking infrastructure remained at the old location, myself and one other employee stayed behind for several months– working alone in a vacant building. For the first few weeks I thought the arrangement was great. I dressed down. I wasn’t constantly harassed or distracted by coworkers. I could listen to music at my desk at a volume I enjoyed. It felt like working from home. Except I was surrounded by dust and growing debris. And a silence that began to trouble me.

By spring I found myself experiencing a dread about coming to work that I’d rarely ever felt in my life. I was anxious and felt totally defeated. I wasn’t exactly sure why. Something about being left behind to work in an abandoned building began to trigger all my most cynical existential meditations. Is this what had become of my professional life? Was I being marked for demolition along with the bricks and mortar?

On May 3, 2024– alone in my office– I got in line for tickets to one of five Madison Square Garden shows in November. The process couldn’t have been more different from 1984. No sleeping on sidewalks—just an early morning queue on Ticketmaster’s website from the comfort of my office chair. At 9:50am , a little counter told me I was 34,000th in line. I remember almost crying in frustration. Apparently people from all over the globe were trying to get tickets at the same time. I came to grips with the reality that there would be no second row seats in my future. History wouldn’t repeat itself.

At some point that afternoon, when I’d given up all hope of going, an additional show was announced. My wife quickly jumped in line and somehow nabbed decent seats about halfway up the incline of MSG, for $350 each.

I was going to see Dave!!!

As spring faded into a sweltering summer, things got nightmarish. It turns out, that being left behind in an abandoned building IS actually a sign that you’re next. Management were indeed considering outsourcing my department. We were starting to be viewed as artifacts of a different time— old structures whose usefulness had perhaps come to an end. Throughout June and July, every day at work was a tightrope walk across the deep ravine of redundancy and obsolescence. I walked up the steps of my new office in the trailers every morning, never knowing for sure whether it was my last at the company.

The new Gilmour album was released in September and it surprised me. It didn’t sound like a man at the end of his career. Nor did it sound like someone begging to be relevant. The whole album sounded like someone boldly doing what they’ve always done — and enjoying himself in the journey.

In the devastating closing track, Scattered, Gilmour unflinchingly addresses the sweeping tides of old age and mortality. It’s the first time in decades that he’s played and composed music with this kind of confidence. The tune opens with minimalist piano lines pinging through the rotary speaker of a Leslie cabinet– an obvious homage to 1971’s Echoes and the memory of the late Richard Wright, close Gilmour friend and long-time Pink Floyd keyboardist. In spirit, Rick is all over the monumental closing track. But oddly enough, so are we.

Gilmour invites listeners in the opening verse, with a noticeably husky, age-worn voice,

Take my arm and walk with me

Once moredown this dusty old path

The sunset cuts the hill in half…

The light’s fading, you say

But these darkening days

Flow like honey

As the concert date approached, my outlook at work changed. With nothing to lose, I pushed back against my own fears. I reached out warmly to the very people at work who were behind the scenes, plotting my demise. I stopped acting like a man headed to the gallows. I reached out to others, instead of retreating into a cocoon of self-sabotaging isolation . And a weird thing happened. Things got a lot better. I got better.

Each listen to Luck and Strange during those tumultuous weeks, deepened my appreciation for the journey that led me to this strange station of life. Yes, I was the “old guy” now at work. Yes, there were more days behind me than before me. But I still had fire in my belly. And I was going to NYC to see Dave.

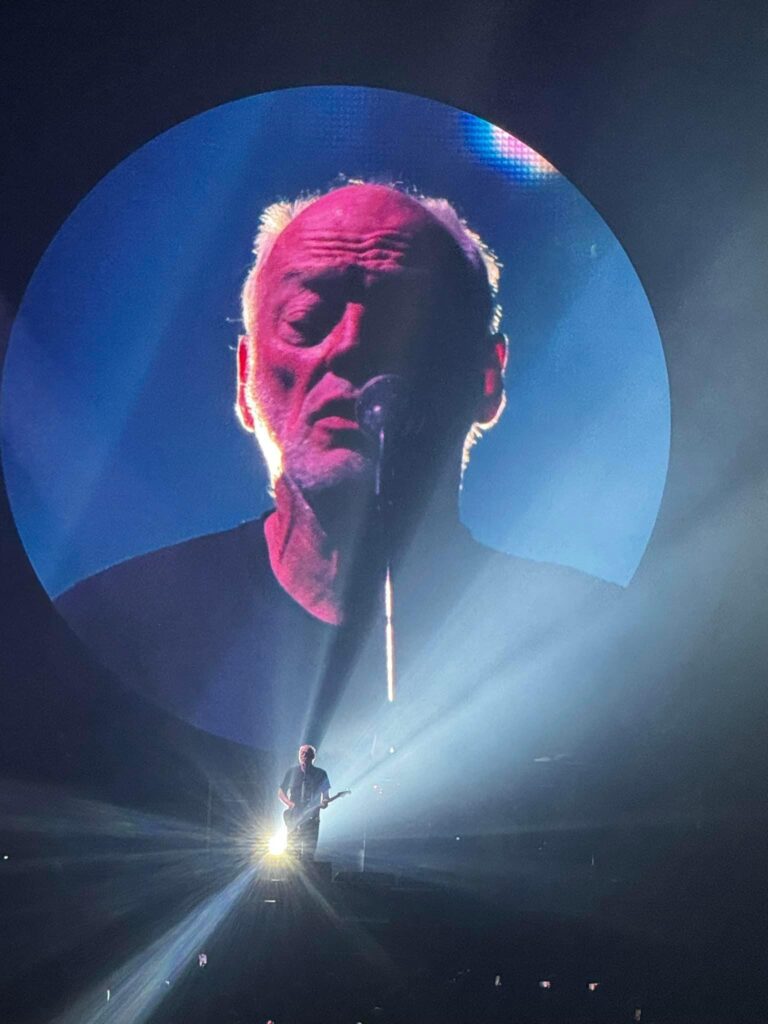

Sitting in Madison Square Garden, surrounded by thousands of other fans, many who were my age or older, life had come full circle . There was an old man sitting behind me with his grown kids who had last seen Pink Floyd when I was a small child. There was a married middle-aged man from Argentina who sat next to me with his wife, who kept wiping away tears all night. The prospects of this gathering were all the same– we were all fading together slowly, but holding tenaciously to equal measures of hope and expectation. To hell with doom.

Gilmour took the stage to the instrumental 5am. A simple tune, effectively told as a rising beacon shone on the frame of a solitary figure at center stage. He went on to rip through classics like Time and Fat Old Sun with an earnestness that repeatedly made the water rise in my eyes, but most of his focus was on the new material. And it was sublime. All of it.

None of it felt like a cover band. Inexplicably, it felt like Gilmour in his heyday– something I hadn’t experienced in 1984.

The quiet, extended lap steel portion of the show– an unspoken tribute to Rick Wright– where he played Great Gig in the Sky followed by A Boat Lies Waiting, remains one of the most powerful concert experiences I’ve ever had. Period.

And then there was this moment at the end of the show.

If I hadn’t been there and seen it myself, I frankly wouldn’t have believed it.

The second setlist’s closer, Scattered, featured Gilmour confessing his own losing battle with entropy:

A man stands in a river

Pushes against the stream

Time is a tide that disobeys

It disobeys me

Following that melancholy resignation in the lyrics, the 78-year old man in the spotlight kicked on one of his boost pedals and the hair-raising wail from his black Stratocaster filled every square inch of the Garden– paradoxically giving that tide no choice but to obey him. Even if for just a moment.