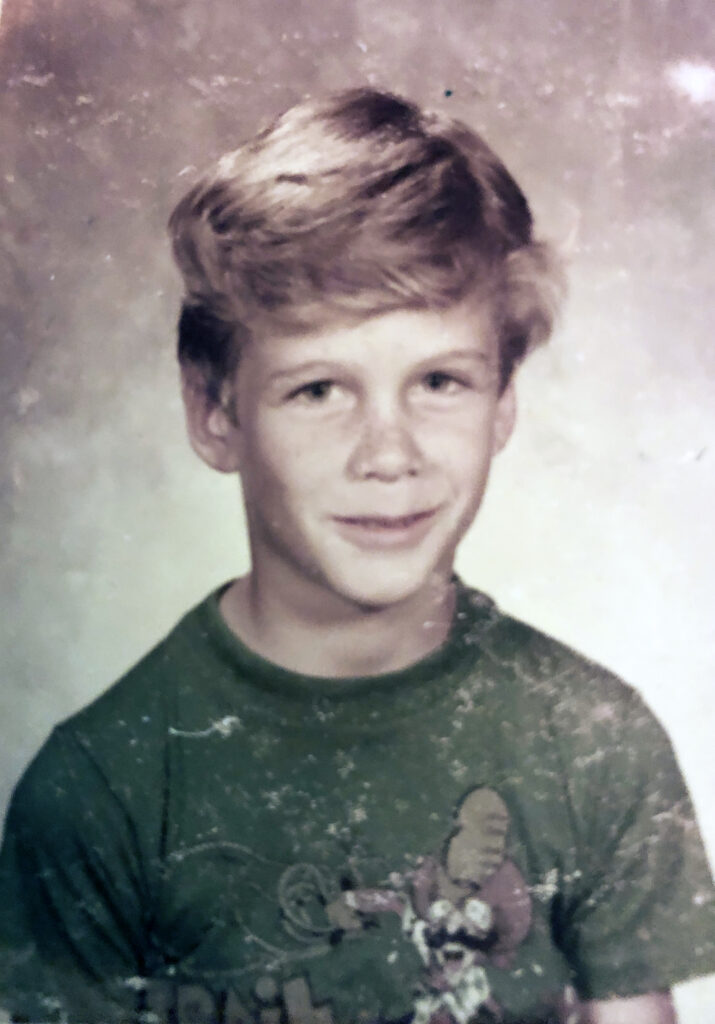

1976 ended up being a tumultuous year for me. I was 7 years old. I loved playing with G.I. Joes and watching Gamera and Godzilla movies on Creature Feature. I poured over my collection of Silver Age Marvel comics like they were the Dead Sea Scrolls. I liked to draw pictures of helicopters shooting giant robots. I believed in Bigfoot and still slept with an assortment of well-loved stuffed animals. Then my parents got divorced.

Divorce is supposed to be traumatic for kids and I reckon for most, it is. For me, that wasn’t the case. I was relieved when my parents split.

Mom and Dad had been arguing a LOT behind closed doors and the anger around the house was smothering at times. When my parents finally brought my younger sister and I into their bedroom to tell us they were separating, my first question– which accidentally burst out of me in a rush of excitement– was, “Does this mean Dad’s leaving???” My Mom answered “Yes”, and looked at me sideways, with a raised eyebrow.

It was totally true. Once Dad got banished to the infamous Palmetto Golf Club Apartments in Perrine, the bad mojo left and things felt easy again. We ate more fast food for dinner. Mom seemed less concerned about chores and homework. I got to watch more TV and stay up late. We got to spend more time with our grandparents, whom we adored.

Marc Chagall, Sher Beedies & Kahlua Cocktail Hour with Kiril

We were also immediately subjected to an alternate version of Mom known as Single Mom, which wasn’t great. At all. This new persona was prone to speaking in a Mid-Atlantic accent –especially after a couple martinis– and was focused on going out on the weekends and leaving us with Katy Murphy, the tubby teenage neighbor. During the few, short weeks that Katy babysat us that summer, I organized a strike and enlisted my sister and my best friend Jeff. The three of us built signs that said “Kids on Strike!” and “Katy Murphy Must Be Stopped!” and walked up and down the sidewalk in front of our house protesting– while Katy watched in horror, through parted curtains.

Around this time, we were also forced to endure Single Mom’s new boyfriend— a creepy Bulgarian artist, with an overly-neat Anton LaVey goatee, named Kiril. He was a professional painter, who spent a lot of time making perfect Marc Chagall forgeries and smoking thin Indian cigarettes called beedies. For me, he was a soft target.

For a while that summer, the guy seemed to spontaneously appear in our driveway at the most inopportune moments. Mom would eagerly announce his arrival, like Elvis was coming for dinner– “Kids! Kiril is here!” Neither my sister nor I would move a muscle. Our inaction always brought on her follow-up trumpet blast, which seemed to rip through the fabric of space-time: “SAY. HI. TO. KIRIL. NOW!!!”

After two hours of hearing his effete Bulgarian ass, blathering on and on about Paris while the two sipped Kahlua cocktails in the kitchen, Mom would announce, “Kids! Kiril is leaving!” We never moved a muscle.

Mercifully, it didn’t take too long. One day, goofy ol’ Kiril just stopped appearing in our driveway and Mom didn’t mention him again. She kept all his Chagall prints, though.

During that weird time in our lives, adults seemed to be perpetually leaning into my personal space and asking how I was doing– with that waxy, patronizing, grown-up face. My brain was shouting “I’m fine!”, but for some reason that wasn’t what they heard. In their imagination, I was holding in a black reservoir of sadness. Grown-ups love reading into things.

In August, shortly after Dad’s exile and right after Kiril’s blessed rapture out of our kitchen, I started 3rd grade.

As fate would have it, I commenced the new school year under the worst teacher in the history of Pinewood Acres Elementary School– Mrs. Betty Sheffield.

It’s amazing how I second guessed using her real name for this, some 47 years after the fact. Was she really that bad? Do I still hold some kind of primal, childhood fear of her reprisals?

Yes. And yes.

Which is why saying this, after so many decades passed, is nothing more than the “bravery of being out of range”.

Pinewood Acres was an early Dade County, frontier-style private school. It was situated on a large parcel of land in Kendall, which in the early 70’s was still a somewhat rural location. The property had horse stables out back and a permanent corral. It was the perfect place to play hide and seek and interact with nature and get filthy– which to me, gave it the rustic, homespun charm of a Mark Twain novel. There was a rifle and archery range on the backside of the property– which was only used for their summer camps– along with remnants of an old wooden garage, with some kind of rusted-out 1940’s F-Series Ford pickup inside, just sitting on blocks. The whole place was full of hidden corners and off-limits areas to explore and find trouble– which I did with abandon. Including once getting riddled with a ferocious case of poison ivy.

There was no large, monolithic school building anywhere on the property, but classrooms consisted of these little bungalow-style buildings, some of them connected, but all of them situated in random spots throughout the wooded property. It’s like the whole place had maybe been a remote hunting lodge back in 1920’s or 30’s.

1976 was Betty Sheffield’s first year of teaching. She was from West Virginia, or some place in that neighborhood. She spoke with a banjo-pluckin’, backwoods twang– which in South Florida at the time, seemed like a foreign language to me– and wore short-cropped bangs that rested perfectly in a straight line across the top of her eyeglasses. Her peepers were abnormally close together and she favored neon red lipstick, which even a 7-year old boy could tell wasn’t painted “inside the lines”. She was slim, and her frame was accented with a daily rotation of tight, plaid polyester pants– all of which revealed a pronounced “gunt” (the term didn’t exist then, and is now used vulgarly to describe a bulbous role of pelvic fat). What was it, I wondered? None of the other teaches at Pinewood had one. My mom didn’t have one. I was still mostly in the dark about the female anatomy, and the bulge seemed like an oversized set of poofy, cartoon testicles. I never made fun of it. But I did stare at it in bewilderment, during her lectures at the blackboard.

Mrs. Sheffield’s classroom was a perfectly square bungalow, that sat strangely alone in the middle of a plot of land– almost like some kind of interrogation cell. The room held maybe 10-12 students and had just two tiny windows, which Sheffield kept mostly covered because she resented free thought and daydreaming and fancied a Gulag-style educational model.

My wife has been a public school teacher for 30 years and I know the truth now: teachers, for reasons they can’t always explain, sometimes just dislike certain students. For Sheffield, I was one of those students.

When she reached her breaking point with the class— which was roughly three to four times a week— instead of just excusing herself and having a smoke or walking out to the horse stables to have sex with the school’s Bjorn Borg lookalike tennis instructor, appropriately named Roger Off (an activity engaged in by more than one Pinewood teacher, I would later find out), she’d take out her mid-life rage on me. Most of the time this involved grabbing me violently by the arm and hissing in my face, with her lipstick-smeared choppers and gamey horse breath downdrafting straight into my lungs.

I was sent to the principal’s office on a number of occasions, early on in the school year. Once, unclear about precisely what I’d done to deserve a trip to the executioner, she replied coldly, “I’m just sick of lookin’ at ya.”

For several decades of my life I wore this trademark smirk, which unwittingly telegraphed to teachers like Mrs. Sheffield (and later, to other women in my life), that I was probably up to something. I wasn’t.

I just thought shit was funny.

The King of the Night Time World

Earlier that summer, on a Kiril-free evening, Mom was driving my sister and I to McDonalds, blasting WQAM at full volume with all the windows down. This was because her old, beige Pontiac had no A/C and was only equipped with a crummy Delco AM radio, which had to be cranked wide open in order to hear it over the wind and traffic noises. But it was also because Mom was just 30 years old and newly single. The summer of 1976 was all breezy Seals & Crofts and Afternoon Delight and ABBA, but on the way to get burgers that afternoon something new came out of the backseat speakers that made my little eyes bug out. It was electric and sounded almost feral, next to Dancing Queen.

“What is that sound?!” I yelled over the roar.

“It’s guitar, I think!” Mom volleyed back, semi-distracted. “Wait for the end of the song, the DJ will tell us who it is”.

“That guitar sounds like someone talking!”, I hollered.

There was no edited, single version of “Do You Feel Like We Do” in 1976, so we waited in the car, idling in the McDonald’s parking lot for 14 minutes, before I heard who it was.

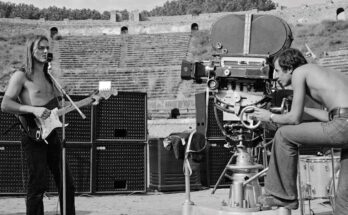

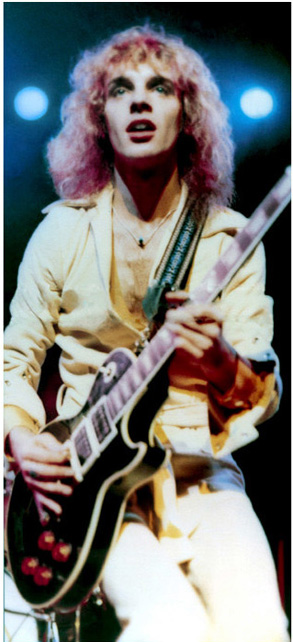

A few days later, Mom drove me to Specs Records in Dadeland Mall, to buy me the now-iconic double album Frampton Comes Alive. It had a big orange sticker in the corner, advertising the sale price at $3.99. I stood next to the record rack in Specs, studying the cover in awe. That black Les Paul custom, with three humbuckers, had to be the source of the magic sound I had heard. We went home and I played the 14-minute track at least 50 times over the next couple weeks, completely entranced. It was magic. And the more I played it, the magic diminished not one whit.

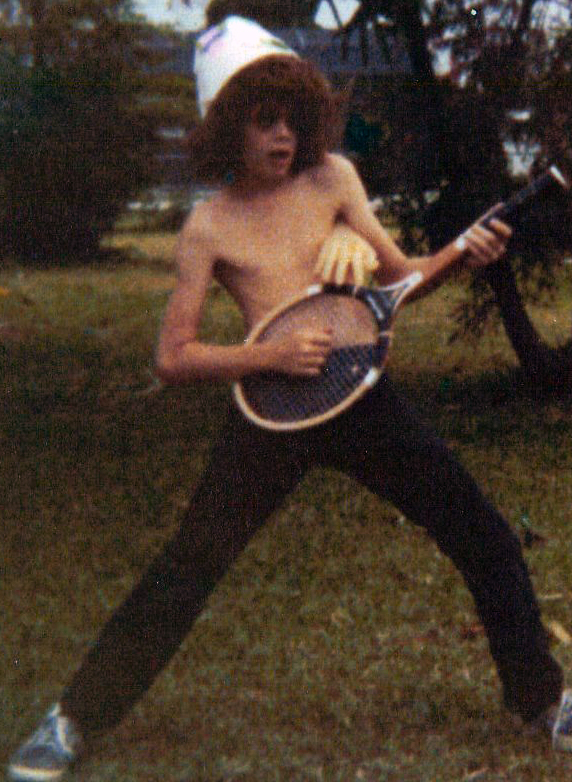

I wouldn’t find out till years later, that the sound I was hearing was a Heil Talk Box; a pedal effect that uses a mouth tube to control the tone output on an electric guitar. My best friend Jeff believed that the weird sound was made by a tube that went down Frampton’s throat into his stomach. Like an electrified stomach pump through a Marshall stack. Jeff had “for sure” seen it on the Midnight Special a few weeks before. Without the benefit of the internet, I had to take Jeff’s word for it, but it didn’t really matter. A light had been turned on. To make those kind of weird noises, with an electric guitar in my hand, was exactly what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.

Our babysitter Katy Murphy, who was a venerable 13-years old at the time, saw the gatefold album cover lying on our coffee table one night and asked me if the record belonged to my mom. “It’s mine”, I said proudly. She informed me that I was way too young to be listening to Frampton– he was for teenagers. Katy and I had a rocky relationship, but that night she acknowledged that she may have misjudged me. I actually had good taste, she told me.

In my mind, I was suddenly in the cool group. The “older kids” faction.

Fast forward to sometime that Fall.

For Show-n-Tell Day, I brought Frampton with me to Mrs. Sheffield’s class, prepared to give my dissertation on the magic of 70’s British guitar heroes, to the group of 7 and 8-year old naysayers and Philistines. By that time, I had memorized every note of Do You Feel Like We Do, every crescendo, every audience whistle, every Frampton shout-out to his backing band (“Pop Blam on the keyboards! Pop Blam!”) What a day it was gonna be!

On that morning, a handful of fifth grade bullies saw me carrying the album before school started. They were only maybe three years older than me, but those goons seemed like grown men. They circled me on the bleachers before the school pledge of allegiance, and drilled me. “Hey kid! Open that album!” I held up the gatefold, revealing the full image of Frampton under those stage lights– his curly hair glowing pink, knees squished together. The bullies all started laughing. I’d never realized until that moment, how girly Frampton actually looked. The sound of screeching brakes was imminent.

“That guy’s a GAYLORD and people who have the album are GAYLORDS too!!!”, the chief troll called out. Other fifth and sixth graders on the bleachers, who had been previously engaged in other conversations, turned around and laughed. The word “gaylord” had that general effect back then. I closed the album jacket and sat down.

When I got to class, all of us looked over each other’s Show-n-Tell items.

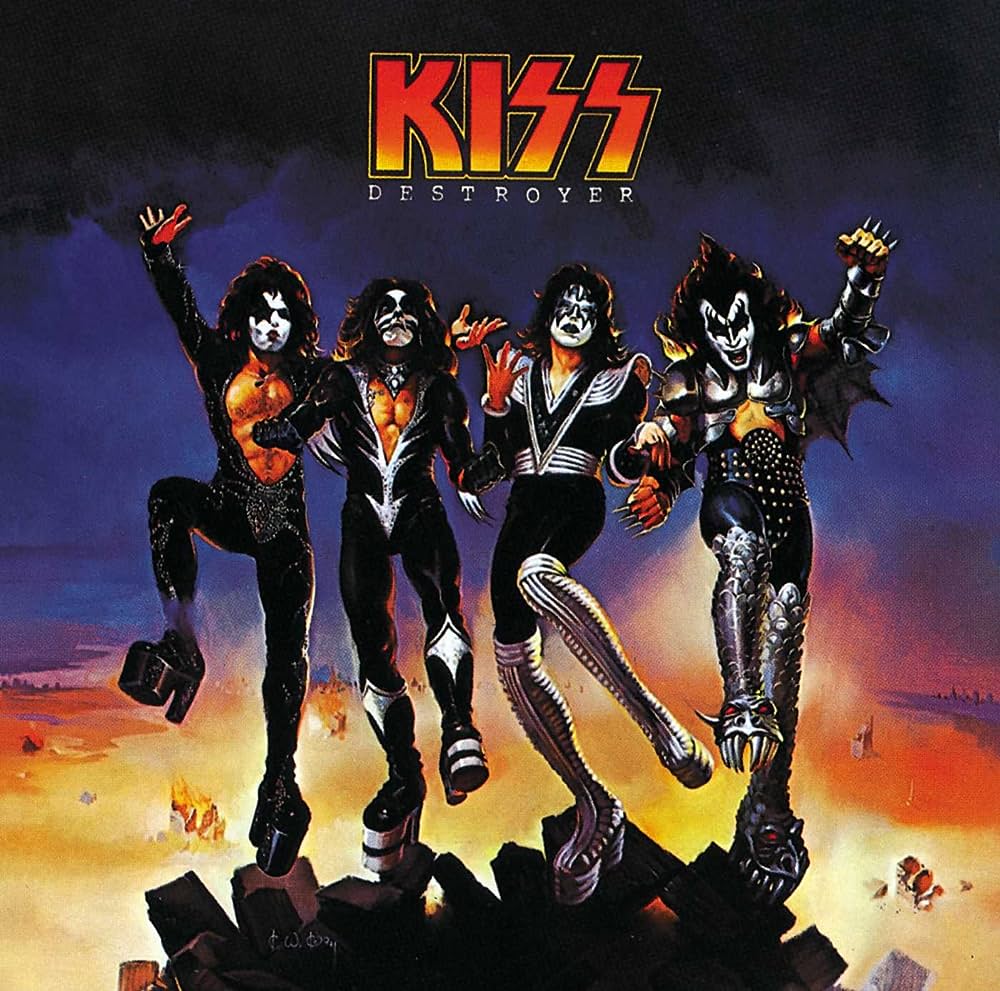

One classmate had a beanbag hippo that had been handed down to them from a grandparent. Another had a trophy from some pottery show. Mark had a photo of his Dad and his uncle with President Nixon. My closest school friend, Spencer, had a set of deer antlers, from the buck that he and his Dad shot on a hunting trip. Only two of us misfits brought in records. There was me with the newly-christened Gaylord Comes Alive, which suddenly seemed incredibly flaccid and airless– and there was Glenn, who brought in some album with comic book villains on the cover. It was called Destroyer and the band was KISS– which seemed like a super girly name for a band. I hadn’t even heard about them yet. Glenn had two older brothers, so he was a lot more in the know about this stuff.

“They breathe fire on stage!”, Glenn informed me, excitedly.

“Which one?”, I quizzed.

Glenn singled out the one with the demon makeup. “He also spits blood!”

“No way!” I protested.

“Yes way”, he said.

“Are those boots real?”, I asked, pointing to Gene’s spiked dragon boots, with the glowing red eyes. Glenn nodded.

The class never listened to Frampton that day. And my lecture on the virtues of British blues guitar heroes was postponed, indefinitely.

I forfeited my 14 minutes of spotlight, and opted instead to let Glenn play TWO songs from Destroyer. Just the song titles got my blood flowing: God of Thunder and King of the Night Time World. The girls covered their ears and grimaced. All my friends gathered in tightly around the portable GE Wildcat turntable, like cavemen around the embers of a growing fire. Best of all, Mrs. Sheffield went into something resembling a febrile seizure while the music played. “That’s Satanic!”, she screeched.

I was SOLD.

I didn’t listen to Frampton Comes Alive for another 30 years. The record eventually got trashed, along with my coloring books and stuffed animals.

I was officially a member of the The Army now.

Post script: Some historical perspective is in order. Frampton Comes Alive may be considered a bit “middle of the road” in 2023, but it remains one of the great live albums of the period, featuring a phenomenal rhythm section and plenty of shining moments of British blues rock . Despite the “pinup” cover and its reputation as a teenage girls album, as a performer Frampton was/is an underappreciated master of improvisational lyricism and phrasing and this album is a remarkable document of that. In my middle age, I listen to it a hell of a lot more than Destroyer.